Recently, I was working on a web application assessment that acted like a feature filled version of the Damn Vulnerable Web App. That meant there was a lot of XSS of course and a heavy handful of SQL injection vectors. This isn’t a post on how terrible the application was but the interesting way they chose to store their password hashes.

Once I found a vulnerable parameter in the application I started to see what the current database user could do. There was no xp_cmdshell, and I was a low-privileged user, so my database access was limited. After a little poking around, I found the table where the usernames and passwords were stored. Almost 118,000 usernames and passwords were present. These numbers are skewed a little since the database stored user’s previous passwords as well as their current password. Regardless, there were still over 104,000 unique hashes.

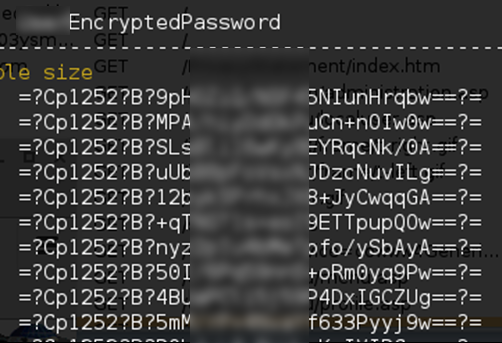

The hashes were stored in a rather curious format. After staring at the hash for a while, a few patterns started to unravel. My first thought was the hash was base64 encoded due to “==” near the end of the string. The other pattern I noticed was the usage of question marks. The question marks seemed to be a field delimiter. The first field would be “Cp1252,” the second field is just a single “B,” and the last field is the base64-encoded hash.

The hashes were stored in a rather curious format. After staring at the hash for a while, a few patterns started to unravel. My first thought was the hash was base64 encoded due to “==” near the end of the string. The other pattern I noticed was the usage of question marks. The question marks seemed to be a field delimiter. The first field would be “Cp1252,” the second field is just a single “B,” and the last field is the base64-encoded hash.

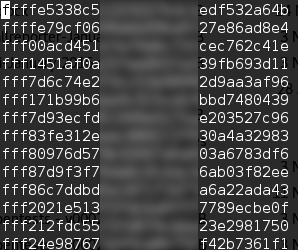

With a little python-fu, I was able to pull out the hashed password, base64-decode it, and then print the hex output. As it turns out, the output was an md5 hash.

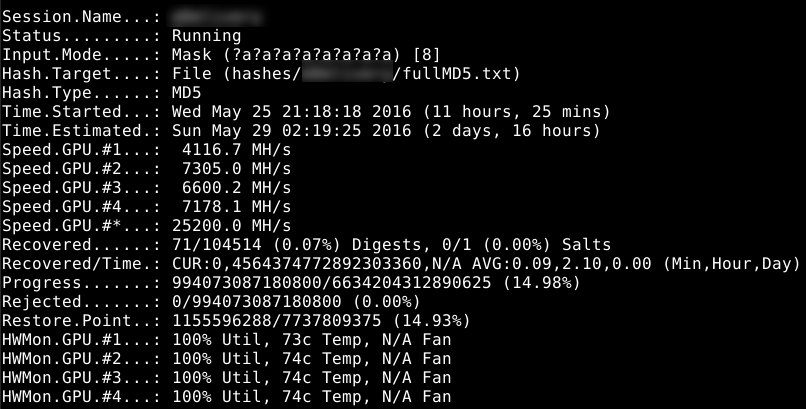

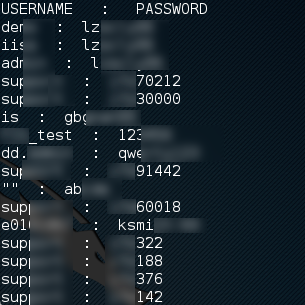

Knowing the application’s password requirements of 10 minimum characters, mixed case, and special characters, I didn’t expect to crack any passwords. To test the waters, I use oclHashcat to run a dictionary attack with the d3adh0bo rule. Within minutes a password was cracked. It was under the password requirement and hope was restored. If I recall correctly, the first cracked password was six characters – three lowercase and three digits. With this in mind, I started oclHashcat as I normally would: first pass with a dictionary and rules like before, the second pass as a pure brute force that increments up to eight characters, and finally a custom mask based off previous cracked passwords modified to only include lowercase characters. To my surprise, we were able to crack 71 hashes for a total of 80 user accounts.

Knowing the application’s password requirements of 10 minimum characters, mixed case, and special characters, I didn’t expect to crack any passwords. To test the waters, I use oclHashcat to run a dictionary attack with the d3adh0bo rule. Within minutes a password was cracked. It was under the password requirement and hope was restored. If I recall correctly, the first cracked password was six characters – three lowercase and three digits. With this in mind, I started oclHashcat as I normally would: first pass with a dictionary and rules like before, the second pass as a pure brute force that increments up to eight characters, and finally a custom mask based off previous cracked passwords modified to only include lowercase characters. To my surprise, we were able to crack 71 hashes for a total of 80 user accounts.

There are a few lessons to learn from this scenario. Encoding isn’t the same as encrypting. When the password policy changes, users and administrators alike should be required to update their password. Passwords should not be easily guessed i.e. not a dictionary word. When hashing a password, they should be salted with a unique and long string. For more information on securing passwords, visit https://crackstation.net/hashing-security.htm.